The Jersey Vindicator

Delaney Hall and beyond: The year in immigration enforcement and its human toll

In the spring of 2025, the Trump administration moved quickly to carry out large-scale deportations of immigrants. By late December, the Department of Homeland Security reported that more than 622,000 people had been removed from the country. At the same time, immigration detention reached record levels, with more than 68,400 people held in ICE custody by mid-December. Most detainees — about nine in 10 — had no criminal conviction.

The Department of Homeland Security launched recruitment drives, including a campaign called “Defend the Homeland,” aimed at hiring 10,000 new ICE officers and expanding the Border Patrol. New technology was rolled out as well, including a mandatory biometric entry-exit system to track noncitizens entering and leaving the country.

Federal agents were also permitted to carry out civil immigration arrests without wearing visible identification or showing warrants to the people they detained. In many cases documented this year, agents approached people in public places or outside courtrooms, identified themselves verbally as federal officers and took individuals into custody without presenting paperwork, relying on administrative authority rather than criminal warrants. Attorneys and advocates said the practice made it difficult for families and bystanders to understand who was making the arrest or on what legal basis.

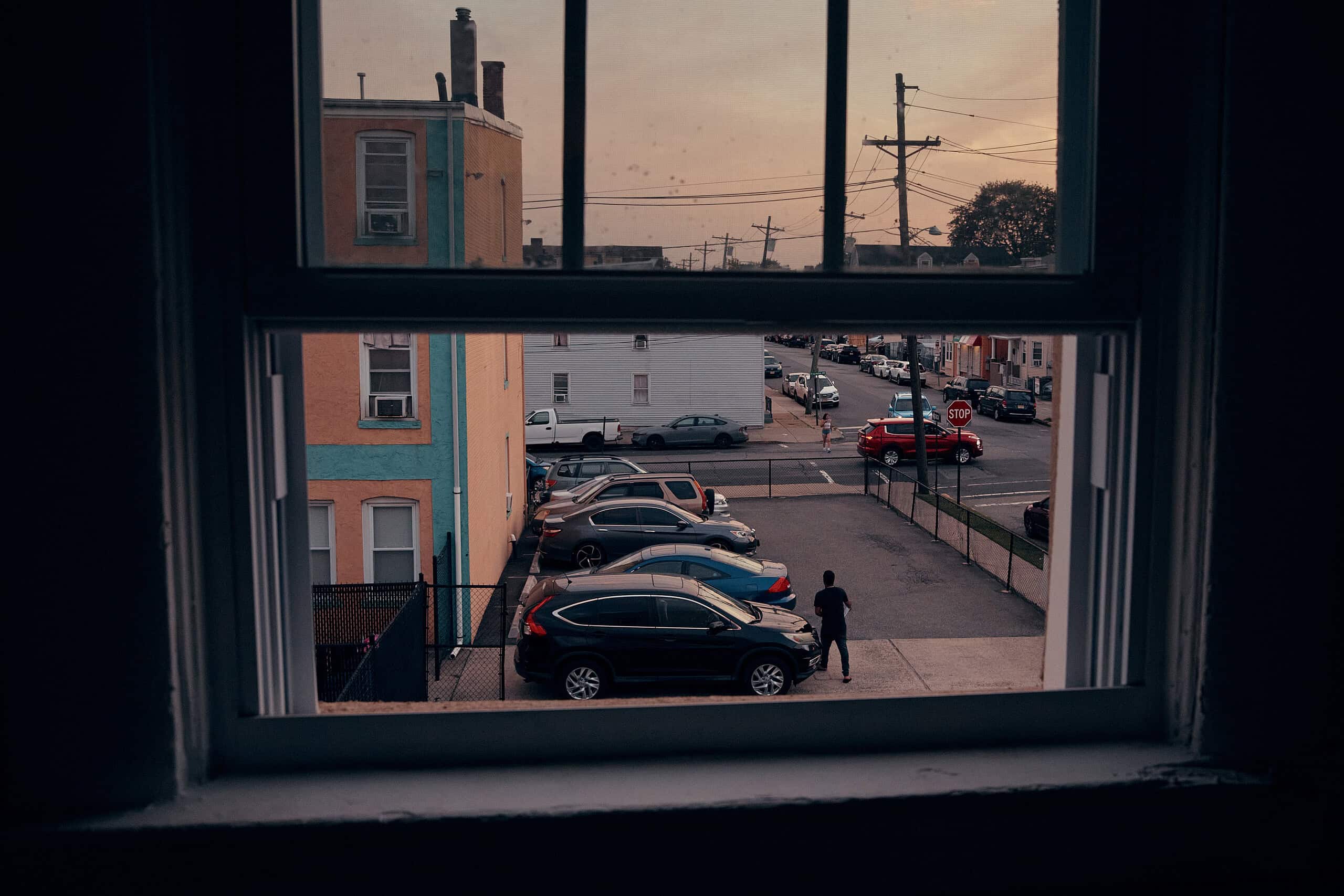

In the New York–New Jersey metro region, immigration enforcement expanded sharply, in part because both areas are long-standing hubs for immigrant communities, large numbers of asylum seekers, and long court backlogs. In New Jersey, the reopening of Delaney Hall in Newark — a former private prison run by the GEO Group — as a1,000-bed detention facility drew particular scrutiny. The facility held as many as 859 people at one point in 2025 under ICE custody. ICE arrested more than 5,300 people in New Jersey since Trump took office, one of the highest totals of any state, and Delaney Hall became a flashpoint for protests and legal challenges over detention conditions and oversight.

For the detained, the process often moved quickly. For families, the effects were immediate and long-lasting. A person would leave home for a court hearing, a shift at work, or a routine errand and not return. What followed was a period of uncertainty for families about where loved ones were being held, whether they could speak with a lawyer, and how to manage the practical consequences of detention, including lost income, disrupted childcare, housing instability, and prolonged separation.

The Courts

On weekday mornings, immigration proceedings take place inside federal buildings across the region. In Lower Manhattan, hearings are held primarily at 26 Federal Plaza and 290 Broadway.

In Newark, immigration court operates on Broad Street, inside a federal building where judges have barred photojournalists.

Before hearings begin, families sit in court waiting rooms clutching folders thick with paperwork meant to demonstrate compliance such as proof of address, hearing notices, and affidavits.

Children sit on plastic chairs or sleep in their parents’ arms as judges cycle through long dockets behind closed doors.

These are the places where people come to ask for asylum, challenge deportation orders or return again and again for brief hearings that can determine whether they will be allowed to stay in the country or be forced to leave.

Inside the courtrooms, judges issue brief rulings and set future court dates that can be months or years away.

Interpreters move between rooms. Attorneys step in and out of hearings. Sometimes, relatives in waiting rooms watch doors open and close, unsure whether the loved one who entered will walk back out with a new court date — or not at all.

In the corridors, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents wait. They position themselves just outside courtroom doors, mostly masked and in groups.

Attorneys, volunteers and court observers say the agents know exactly who they are waiting for and when hearings will end. Sometimes they also approach random people who look like immigrants.

At 26 Federal Plaza, after immigrants are approached stepping out of a hearing room, federal agents confiscate their backpacks and personal belongings, and separate them from their relatives.

Some are escorted silently toward elevators crowded with agents and takentemporary holding area. Others are handcuffed and led down stairs. At 290 Broadway, the pattern is the same.

Roger Tamayo Campos

Late one afternoon on the 13th floor of 290 Broadway, guards changed shifts outside an immigration courtroom. Five ICE agents waited nearby for Roger Tamayo Campos, a former Marine from Peru who was seeking asylum. Two of the agents spoke Spanish with Latin American accents.

When Tamayo Campos exited the courtroom, agents arrested him and escorted him to an elevator. His lawyer was present, and his car remained parked outside. The doors closed. From there here was taken to Federal Plaza.

Dwight Sequera

In June of 2025, Dwight Sequera, a Venezuelan asylum seeker, was told by a judge that his next hearing would take place in 2026. Minutes later, agents approached him and asked for his passport and backpack.

His wife, Yhornelis Torres, held up his court paperwork in her hand and showed it to them.

“He has his next court date,” she said.

The agents did not respond.

That night, Sequera called his wife from inside 26 Federal Plaza.

“They gave us a little water, sometimes an apple,” he told her. “Some men hadn’t eaten in days.”

In Newark, arrests after immigration hearings follow the same pattern but are rarely witnessed. Unlike the federal court buildings in Manhattan, photography is prohibited. Families often report that they learned that their loved whee detained after court appearances end, without documentation or explanation.

From court to custody

After arrests inside federal court buildings, detainees are often held in rooms with dozens of immigrants packed together. Food is limited. Bathrooms are shared by a large numbers of detainees, and phones are confiscated. During this period, agents circulate paperwork urging people to agree to voluntary deportation before they are transferred to a detention facility.

By evening, those arrested in the Manhattan and Newark federal courts are often no longer there. Within hours, they are packed into vans or buses and taken to immigration detention centers in New Jersey, Brooklyn or Pennsylvania, often without families being told where they are being taken or when they will be able to make contact. Lawyers often learn of transfers only after clients fail to appear for scheduled hearings.

Many detainees are taken first to the Elizabeth Detention Center near Newark Liberty International Airport before being transferred elsewhere. Others are moved directly to Delaney Hall, one of the largest immigration detention facilities on the East Coast.

Delaney Hall

Delaney Hall, a privately run immigration detention center operated by the GEO Group, reopened in Newark under a long-term federal contract. ICE signed a 15-year agreement with the GEO Group, which has estimated the total value of the contract, including cost-of-living adjustments over the life of the agreement, at about $1 billion.

The contract authorizes the GEO Group to detain people on behalf of the federal government in exchange for per-detainee payments, with costs tied to daily population levels rather than length of stay. Delaney Hall has become a central hub for immigration detention inthe Mid-Atlantic region.

Under the agreement, the GEO Group is responsible for day-to-day operations at the facility, including housing, feeding, and providing medical care to the detainees. ICE retains oversight authority and sets detention standards, which are enforced through inspections, audits and contract monitoring. The facility is subject to federal compliance reviews, though advocates and attorneys have questioned how consistently those standards are enforced and how much information is made public.

Detainees arrive at Delaney Hall from multiple points: immigration courts, ICE check-ins, traffic stops, workplace arrests and home raids. Some are transferred within hours of arrest. Others arrive days later, after being held temporarily inside federal buildings or moved through other detention facilities.

On visiting days, families line up for hours in a small parking lot bordered by chain-link fencwa and barbed wire. There is no indoor waiting area.

Visitors report there is no shade in warm weather and no access to bathrooms or drinking water while they wait. Guards periodically open the gate and call out names, admitting visitors in small groups.

Inside the facility, detainees describe conditions that advocates say have steadily deteriorated. Meals arrive at inconsistent hours, and detainees report long stretches without food. When meals do arrive, they are sometimes cold, frozen or spoiled.

“No one ate it,” said Kathy O’Leary of Pax Christi, recalling a lunch detainees described as smelling “spoiled and unrecognizable.”

Detainees have also reported that tap water tastes metallic, with bottled water being available on an inconsistent basis. Hygiene supplies, including soap and toilet paper, sometimes run low.

Medical care has been a recurring concern, detainees and advocates reporting delayed appointments, missed prescriptions and difficulty accessing treatment for chronic or ongoing conditions.

Concerns about conditions at Delaney Hall have been raised repeatedly through complaints to ICE, visits by members of Congress and advocacy organizations, monitoring groups, and legal filings.

Attorneys representing detainees have alleged inadequate medical care, poor sanitation, and barriers to attorney access. Some complaints have focused on delays in treatment and the impact of frequent transfers on the continuity of care.

Delaney Hall Uprising

The gate becomes the battlefield

Tensions at Delaney Hall intensified in early summer. Complaints about conditions inside the facility mounted as population levels increased, and access for families and attorneys remained limited.

In June, detainees at Delaney Hall reported going more than 20 hours without food. Accounts from inside the facility described growing frustration as meal deliveries were delayed and requests for information went unanswered.

Those pressures erupted into a June 12 confrontation that drew public attention to the detention center and was followed by a wave of rapid transfers out of New Jersey.

Arguments broke out among detainees. Guards attempted to restore order as the situation escalated. A confrontation involving dozens of detainees followed, during which property inside the facility was damaged. Four men escaped during the unrest..

Outside the detention center, family memberes waiting for scheduled visits sensed something was wrong. Visits were halted. People waiting in the parking lot reported an increased law enforcement presence and conflicting information about what was happening inside.

As word spread, protesters gathered near the facility and blocked the entrance..

Federal agents repeatedly came outside to clear the gates and reopen access to the facility. Over several hours on the evening of June 12, confrontations between law enforcement and protesters intensified.

Agents raised batons and deployed pepper spray against protesters and journalists. Floodlights illuminated the perimeter as night fell.

In the days that followed, ICE agents began transferring detainees out of New Jersey. The transfers often took place overnight and without advance notice to families or attorneys. Detainees were sent to facilities in Louisiana, Texas, Colorado and New Mexico, according to attorneys and advocacy organizations.

The transfers scattered many people who had been detained in New Jersey across the country, complicating loved ones’ efforts to locate them, maintain contact with legal counsel, and continue work on ongoing immigration cases.

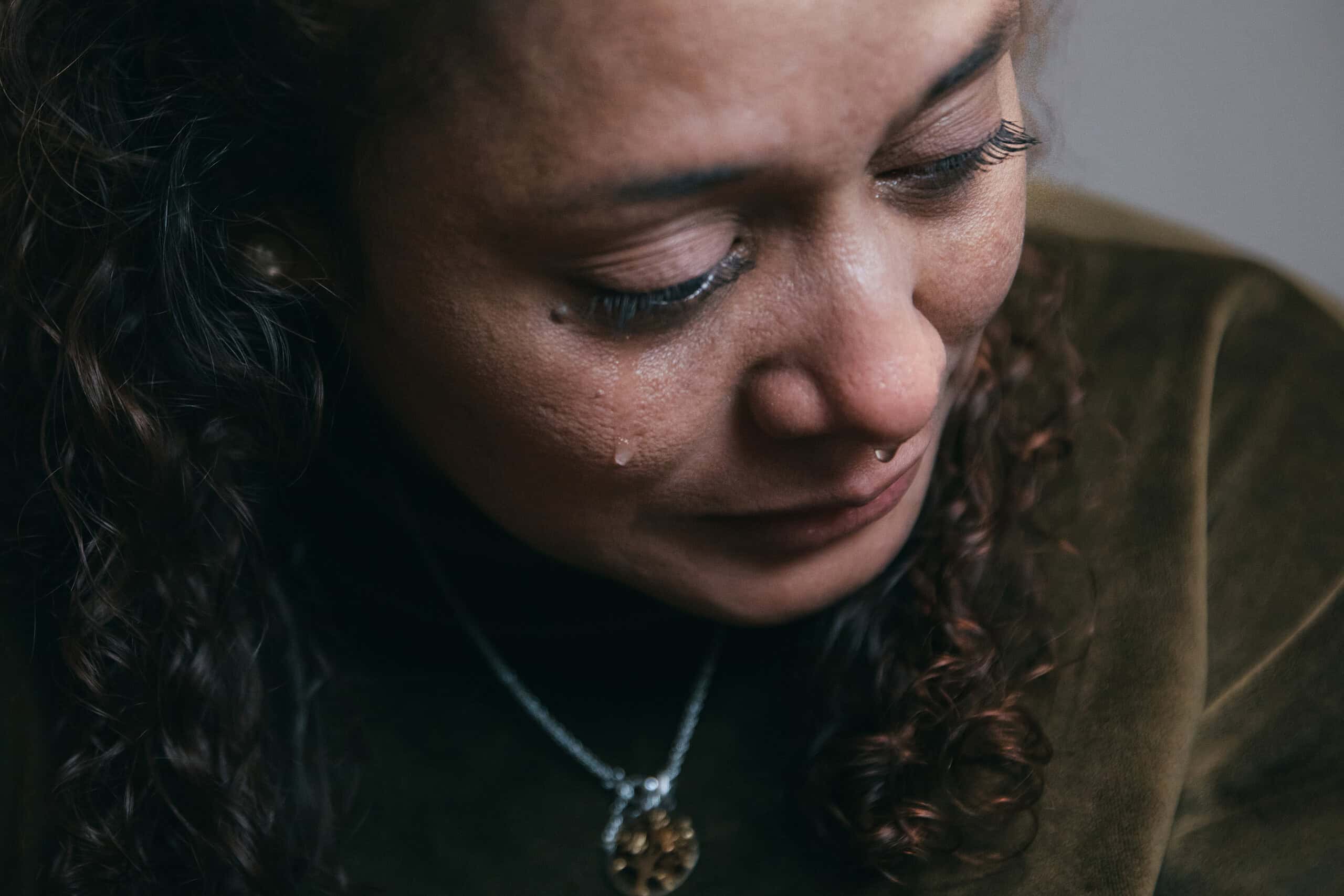

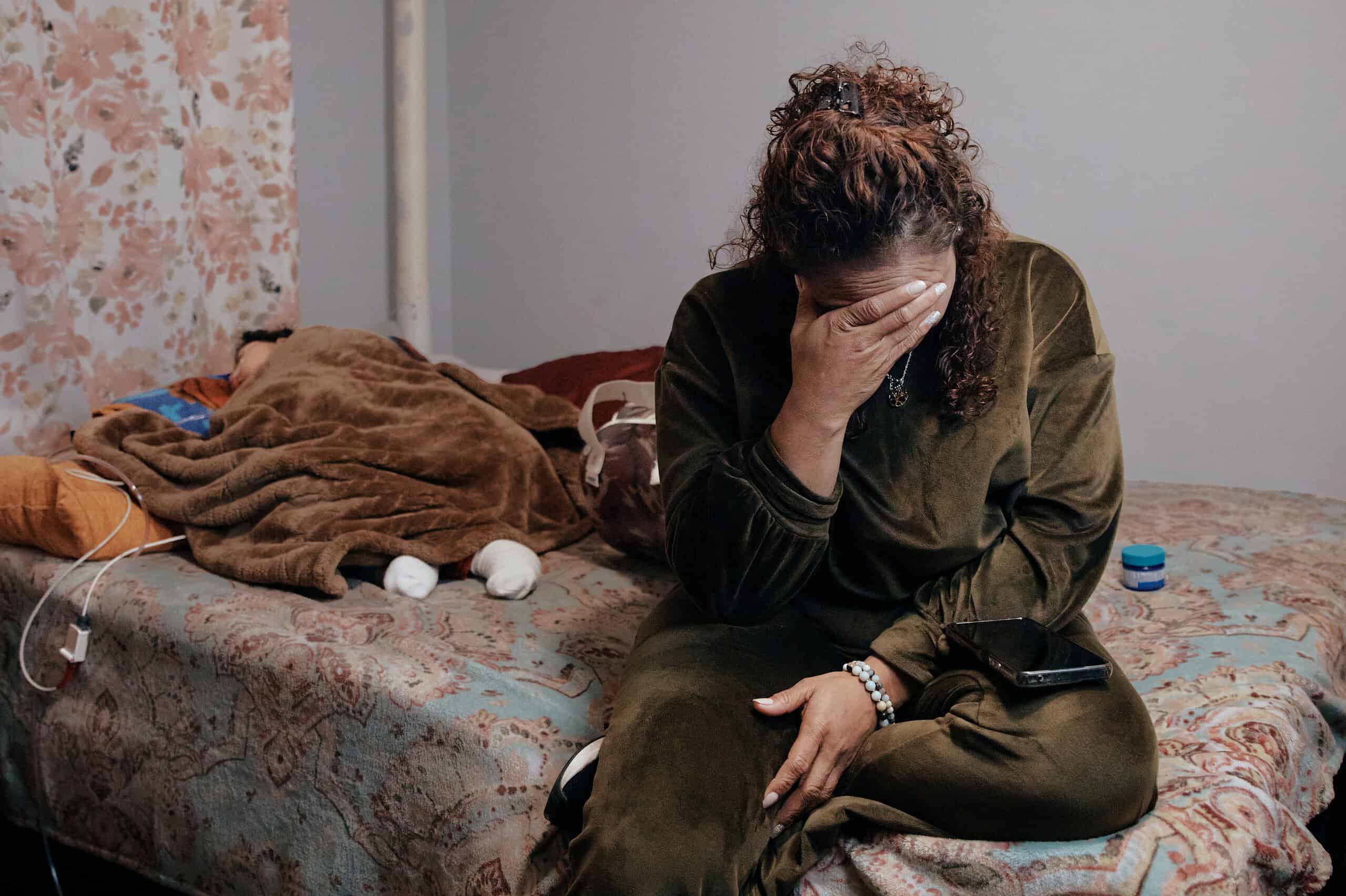

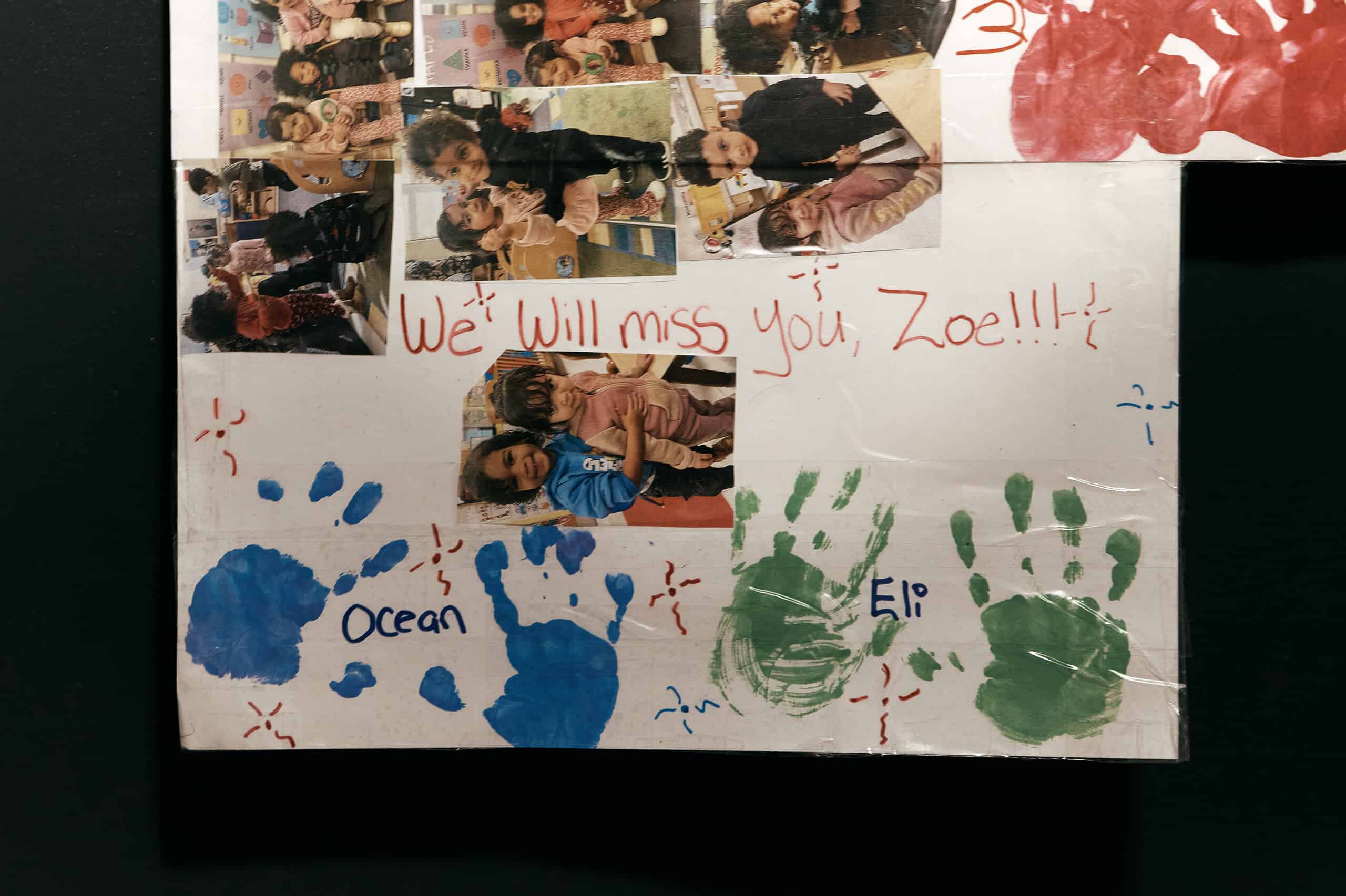

The impacts of detention and deportation are felt most directly inside individual homes, where an arrest is experienced immediately as the absence of a loved one. A parent leaves for a court hearing, a shift at work or a routine errand and does not return. After the initial crisis, families face a series of practical and emotional adjustments that unfold over days and weeks.

These experiences often follow a familiar pattern. Income disappears. Childcare arrangements fall apart. Housing becomes uncertain. Medical appointments are missed. Families wait for information that is frequently delayed or incomplete.

The profiles that follow document how these disruptions have played out in the lives of families across New Jersey and New York.

Families left behind

Fanny Núñez spends most of her time inside a single room in New Brunswick caring for her young son, who relies on an oxygen tank and feeding tubes for his survival.

On Oct. 1, her husband left early in the morning, as he often did, to pick up medication for their son’s seizures and drive a young man he sometimes took to work.

Minutes later, he was pulled over by ICE agents and arrested.

Alejandra’s husband Mauricio was denied asylum after three immigration hearings. At the final hearing, María said, the judge didn’t allow any testimony. He was deported and sent back to Columbia.

Jose Isaias Lopez had lived in Princeton for three decades. He worked as a landscaper and held a valid work permit. During a traffic stop involving a company van, federal agents detained him and other landscapers who were heading to work.

He did not.

Instead, he was transferred to an immigration detention center in Pennsylvania.

“We told her he was on vacation,” his wife said.

Yhornelis Torres crossed jungles, rivers and borders with her husband, fleeing Venezuela and seeking asylum in the United States. They followed the legal process, attended immigration hearings, and waited.

At an immigration court in Lower Manhattan, a judge gave her husband a future court date. Minutes later, federal agents approached him outside the courtroom and took him into custody.

That night, her husband called from inside the federal building where he was being held. He told her he was detained with dozens of other men, some of whom had not eaten in days. Water was limited. The bathroom was overcrowded, and people sat inside it.

After he was transferred to Delaney Hall, Torres gave up their apartment and moved into a shelter with their infant son. The baby later developed anemia. Medical appointments became harder to manage, and transportation depended on others.

“Alone it is more difficult,” she said.

Jaquelin Castro watched as federal agents arrested her husband, Ronald Vázquez, while he was buckling their autistic daughter into her car seat.

It wasn’t.

Without his income, Castro lost her apartment. Her daughter stopped receiving therapy.

The family had to find a temporary living arrangement., and missed medical and school appointments.

Vanessa Aracena learned of her husband’s arrest when a neighbor ran to her door.

Later, Aracena saw a video showing five federal agents surrounding her husband, Carlos Archila Reyes, on the sidewalk outside their home.

Without his income, she had to move back in with her parents.

The arrest, she said, came without warning and without explanation.

Delaney Hall protests

As immigration enforcement intensified, activists organized protests outside detention centers, on courthouse steps, and in the streets surrounding federal buildings.

Clergy

“Let us see. Let us visit. Let us witness.”

Rev. Anya Sammler-Michael

Unitarian Universalist Congregation

Clergy members gathered outside Delaney Hall wearing stoles, clerical collars and prayer beads. Some knelt on the pavement. Others sat cross-legged near the gate.

They asked to enter the facility to visit detainees, observe conditions and bear witness. They were denied access.

Instead, they remained at the entrance, bodies still and hands folded, forming a quiet line between the detention center and the street. They blocked cars and the entrance. Several activists were arrested.

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka’s arrest

“Let us inspect. Let us oversee. Let us enforce local law.”

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka arrived at Delaney Hall to join members of Congress for an oversight visit.

U.S. Reps. Bonnie Watson Coleman, Rob Menendez and LaMonica McIver were allowed to enter the facility for the tour. Baraka was let inside the gate but was not permitted to go inside the facility for the inspection, and was told to leave.

After he exited the gates, federal agents moved in on him and placed him under arrest. Supporters and lawmakers gathered around him as he was taken into custody.

A judge ordered his release later that night.

“We did nothing wrong,” Baraka said after his release, urging people gathered at the site to go home.

Federal Plaza

On June 10, thousands of people gathered in Lower Manhattan to protest the Trump administration’s intensified immigration enforcement and recent ICE raids. Demonstrators filled Foley Square and the surrounding streets near 26 Federal Plaza, a federal building that houses immigration courts and an ICE field office.

The site has become a flashpoint as migrants attending court hearings have increasingly been detained there.

The protest was part of a nationwide wave of demonstrations calling for an end to deportations. Chants against ICE echoed through the streets as demonstrators marched and rallied near the courthouse.

As the evening wore on, tensions escalated. Police moved in, pushing some protesters to the ground and making arrests.

Canal Street

On Nov. 29, a confrontation unfolded in Lower Manhattan’s Chinatown after residents and activists learned that ICE agents and other federal authorities were gathering inside a parking garage near Canal Street, preparing for a large enforcement action targeting immigrants. Protesters quickly assembled outside the garage, determined to block the agents from leaving and carrying out arrests.

Demonstrators surrounded the entrance, forming human barricades and using garbage bags, wooden pallets, and traffic barriers to obstruct ICE vehicles. They chanted slogans like “ICE out of New York” and blocked agents from leaving

As the standoff intensified, the New York Police Department arrived on the scene. According to police, officers were responding to reports of a disorderly group blocking the street and garage entrance. Many protesters accused the NYPD of facilitating ICE’s efforts by clearing paths for vehicles and arresting demonstrators.

Clashes between protesters, police, and federal agents became physical. People threw debris, and police used force, including nightsticks and pepper spray, to disperse crowds. Several protesters were arrested for failing to comply with police orders.

New York City Council members and community leaders praised the protesters for their efforts to stop the enforcement action, while others criticized the NYPD’s handling of the situation and its interactions with federal authorities. The incident drew attention from New York’s mayor-elect, who urged immigrants to know their legal rights.

What comes next

The federal government’s push to expand immigration enforcement shows no sign of slowing. Officials have signaled plans to continue increasing funding for immigration agents and detention space next year, including through new programs and large appropriations tied to broader spending bills that aim to boost enforcement capacity nationwide. ICE has already reopened and expanded detention space in New Jersey, and federal agencies are weighing the use of other sites — including warehouses and military bases like Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst in South Jersey — to hold people while deportation proceedings continue. Advocates and lawmakers have raised questions about how these plans might affect communities and legal rights as enforcement efforts grow in 2026 and beyond.