A father’s detention leaves a New Jersey mother and autistic daughter in crisis

Just after 7:40 on a Monday morning in August, everything in Jaquelin Castro’s world came undone.

She was in the driver’s seat of the family car with the engine running, preparing to take her daughter to therapy before heading to her part-time shift at a local cafeteria. Her husband, Ronald Vázquez, was off from his welding job in Edison that week. He put a pancake in his daughter’s hand, carried her down the stairs, placed her in the back seat of the car, and leaned in to fasten her seat belt. Then he looked up.

“A police officer is coming,” he said.

Through her side mirror, Castro spotted a masked man approaching. She stepped out of the car only to find two men already behind Vázquez. One snapped a pair of handcuffs around his wrists.

“Why are you doing this?” she asked. One man said her husband had missed a court date — but he hadn’t. “Everything will be explained at the office,” the officers said.

Her husband started crying. Castro could hardly believe what was happening.

“They said they were taking him to Newark,” she told The Jersey Vindicator. “No more details. No paperwork. No time to process anything.”

A call from inside

Later that day, the phone finally rang. Vázquez was calling from Delaney Hall, the immigration detention center in Newark. Another detainee had lent him money to make the call. Vázquez told his wife to contact a lawyer.

“They told him he had a deportation order,” Castro said.

Vázquez feared they might deport him immediately. He told Castro he had met people at Delaney Hall who had signed voluntary departure papers but were still being held there for weeks. He said he was asked where his passport was. He refused to sign anything and told federal agents he was seeking to stay in the country because of his 6-year-old daughter, who was born in the U.S. and has autism.

“The agents told him that would be up to a judge,” Castro said.

Detainees at Delaney Hall are given breakfast at about 5 a.m. but often have to wait until 4 p.m. for their next meal, which is either frozen food or bread and ham, Castro’s husband told her. Medical treatment is sometimes denied. The pressure to sign deportation papers is constant.

“They also pressure them through poor treatment so they’ll give up,” Castro said, recounting her husband’s words.

Life before the arrest

Until that August morning, the family lived in a modest apartment in Dunellen, a town of about 7,000 people. Life was simple.

Vázquez, 28, came to the United States as a teenager after receiving threats in El Salvador. A gang tried to kill him and even came to his school to shoot him. Fearing for her son’s life, his mother, who was already living in the United States, asked him to come north.

After Vázquez crossed the border, he applied for asylum. But as a teenager with no steady work, he couldn’t afford an experienced lawyer. He lost his case.

In New Jersey, he built a stable life, working full time as a welder. His routine was unwavering: work, gym, home. On weekends, he took his daughter outside to play and helped her practice her therapy exercises.

“She was very attached to him,” Castro said. “She ran to the door to greet him when he got home.”

His wages covered the rent and the bills. That stability allowed Castro to keep their daughter in a behavioral therapy class from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays. She received additional therapy sessions for speech and, more recently, feeding. She doesn’t eat regular food and requires specialized guidance.

“He was our financial support,” Castro said. “He paid the rent and the bills so I could take her to therapy.”

Losing a home

Without his income, their world collapsed quickly.

Castro could no longer cover the rent. Within two weeks, she had to give up the family’s apartment. That also meant canceling the early-intervention therapies that had taken place at home two or three times a week.

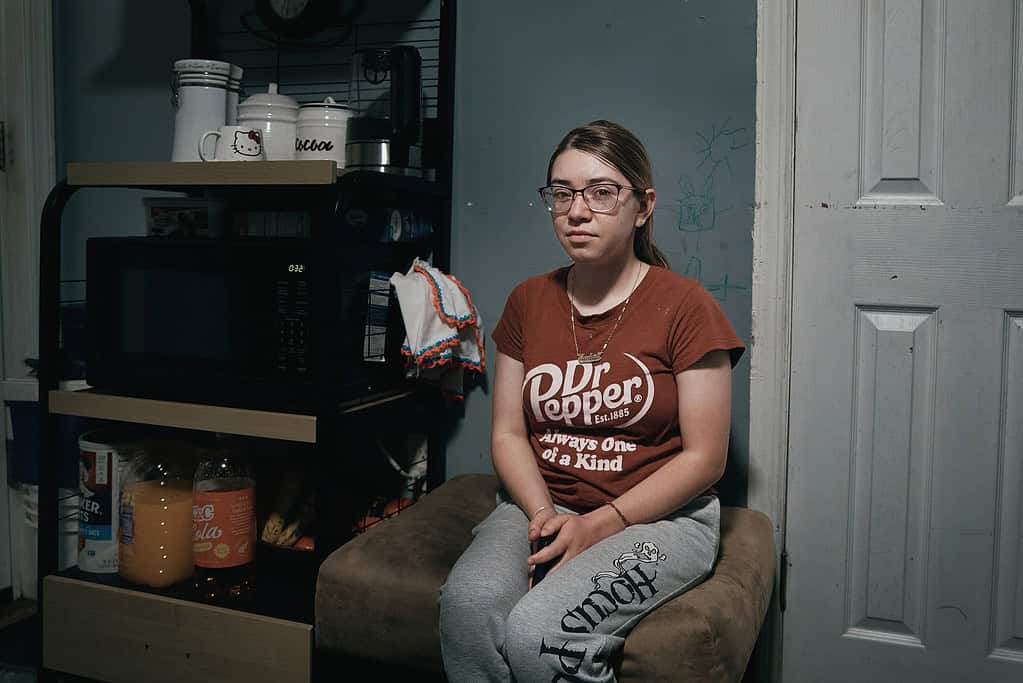

She and her daughter moved into her aunt’s living room, where they now sleep side by side.

“It’s temporary,” she said. “In every apartment, there’s a limit on people. Eventually, I have to find another place for my daughter and me, and right now, we don’t have anywhere.”

Her daughter’s regression was immediate. She stopped eating properly. At school and therapy, everyone noticed her withdrawal.

“Her therapists asked what was happening because she wasn’t progressing. She seemed to be regressing,” Castro said. “I told them about her father’s detention.”

During visits to the detention center, she would light up when she saw her father.

“She’s nonverbal, but when she sees him, she gets very happy. She reaches for his hand, hugs him and wants him to carry her,” Castro said. “When our daughter runs to hug him, he starts to cry.”

Visiting the detention center

Each weekend, Castro made the trip to Delaney Hall in Newark and waited outside for hours with other families before being allowed in. Sometimes Castro’s daughter would grow restless, wanting to leave. The strain of waiting, followed by the intensity of the visit, wore on them both.

“It’s very stressful,” Castro said. “You feel helpless.”

Still, she insisted on going. She knew how much her daughter needed those moments of contact.

“She’s even more attached to him than to me,” she said. “Seeing that hug breaks my heart.”

A family’s plea

Castro does not challenge the government’s move to deport people who commit serious crimes.

“I understand that people who commit crimes shouldn’t be free and may need to leave for public safety,” she said.

But her husband, she insists, is not one of them. He has no criminal record. His only offense was losing an asylum case as a teenager.

“Authorities should focus on criminals, given all the bad things happening,” she said, “not on people who are innocent and have no record.”

Asked what message she would deliver to leaders in Washington, she spoke not as a voter or activist but as a mother.

“I’d ask them to think as parents,” she said. “Many of us come here for the same reasons their families might have — to give our children a better future. For people with clean records who are just trying to build a life, there should be more compassion.”

The weight of uncertainty

For now, Castro works part time and structures her life around her daughter’s therapy schedule. She cannot increase her work hours without sacrificing those sessions. The income gap is still too wide for them to survive on their own.

She has received no direct aid from the local community, though she has been told she may qualify for assistance because her daughter is a U.S. citizen.

“We need a safe place to live and sleep,” she said. “For now, we’re in my aunt’s living room.”

Each day, she makes a calculation to figure out how to stretch her wages, how to prevent further regression in her daughter, and how to keep showing up at the detention center.

“It’s a pain you can’t explain,” she said.

Waiting

Vázquez was detained on Aug. 11. Castro saw him again five days later. Their daughter rushed into his arms. He wept.

He remained at Delaney Hall in Newark, fighting his deportation order, until a few weeks ago, when he was moved to a detention center in Louisiana.

Castro is still sleeping in her aunt’s living room, her daughter beside her.

Her husband once provided for the rent, the groceries, and therapy, and was a steady presence that supported the household.

Now his absence means no apartment, no stability, an autistic child’s loss of skills, and a mother who cannot explain to her daughter why the father who brought her pancakes that morning never came home.

Krystal Knapp is the founder of The Jersey Vindicator and the hyperlocal news website Planet Princeton. Previously she was a reporter at The Trenton Times for a decade.