Five Minutes with Don Torino: Defender of the Meadowlands

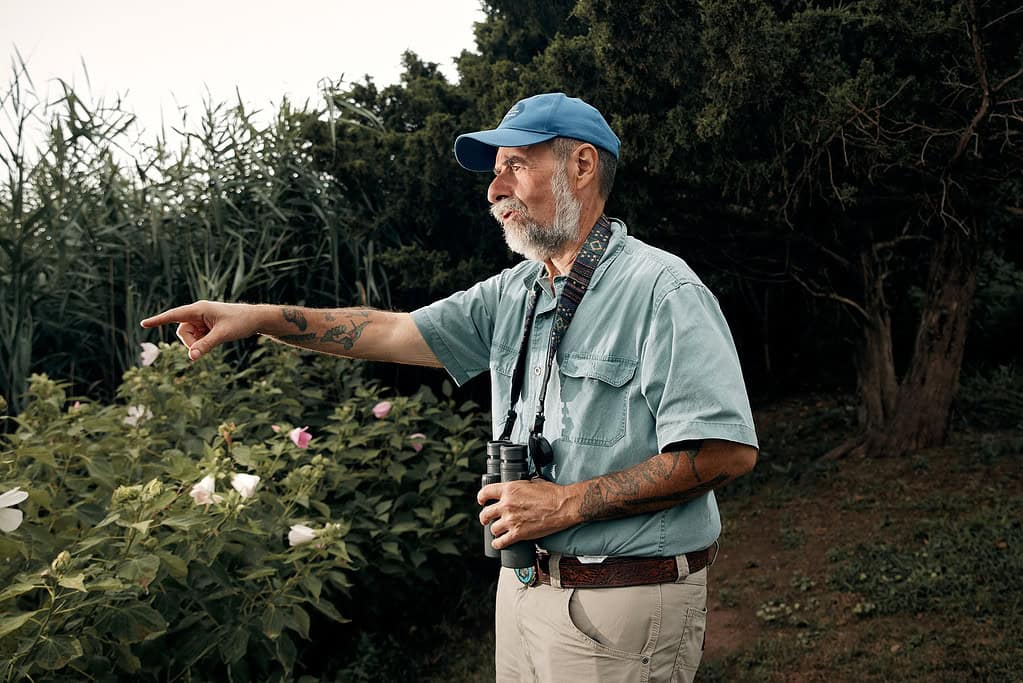

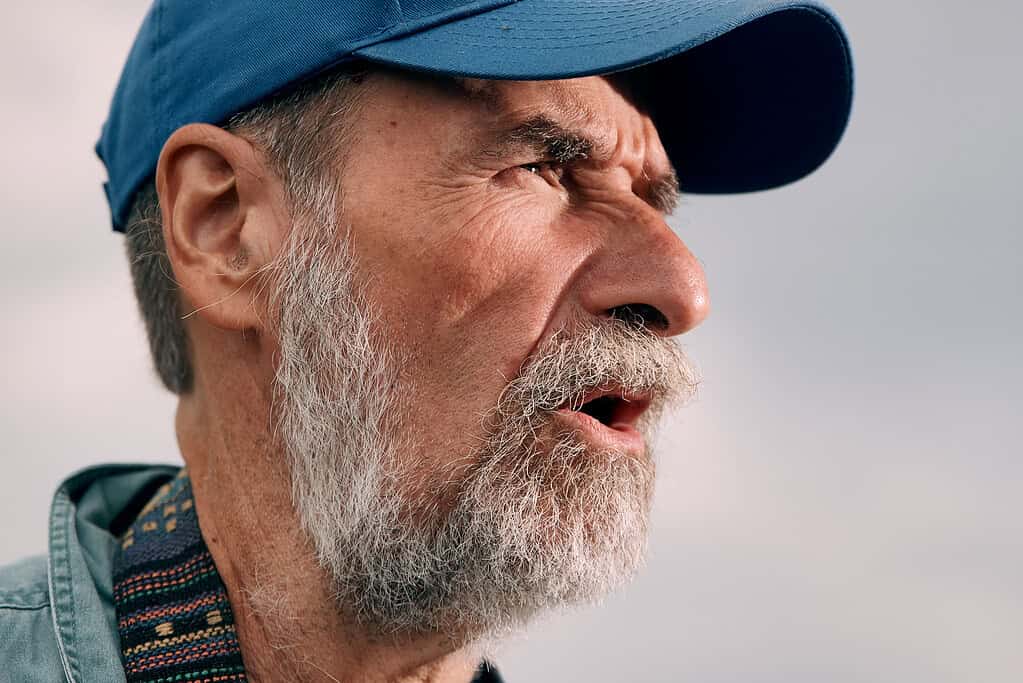

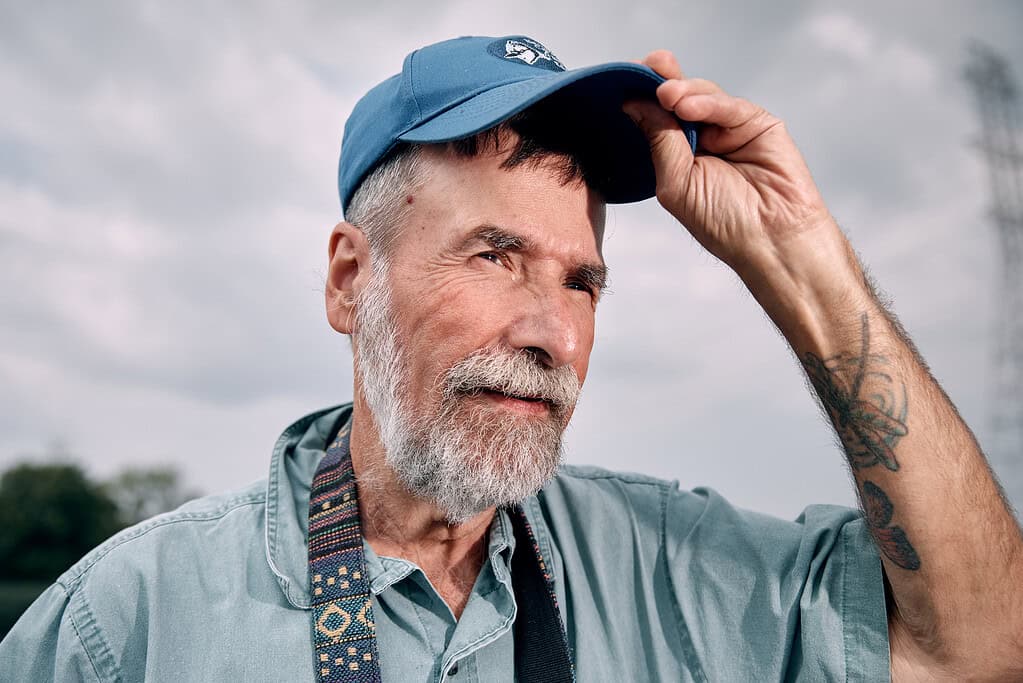

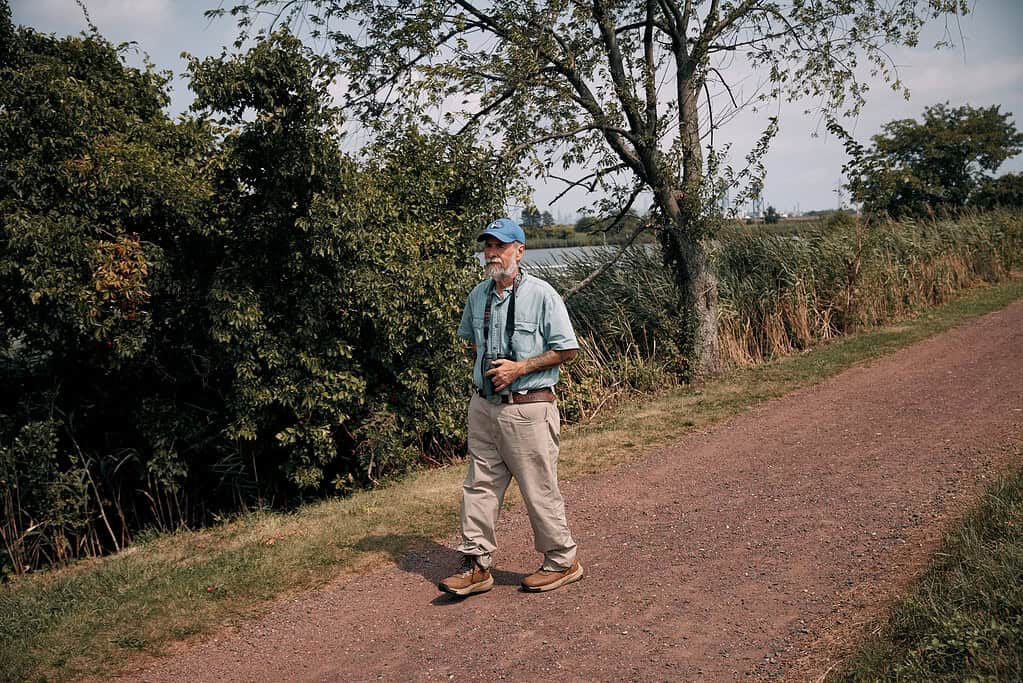

For nearly seven decades, Don Torino of Moonachie has been a soft-spoken but unrelenting defender of the New Jersey Meadowlands, a sprawling tract of swamps and wetlands just west of New York City. The bearded, heavily tattooed Torino — a 69-year-old family man who worked in warehouses, as a labor activist and for Wild Birds Unlimited before his retirement — now serves as the longtime president of the 3,000-member Bergen County Audubon Society. He spends his days trekking through the famed swampland, his binoculars always within reach, and spoke to The Jersey Vindicator last week at Richard W. DeKorte Park in Lyndhurst.

Q: What first drew you to the Meadowlands?

A: I grew up in Hackensack, then my father got ill and we moved to Moonachie, not too far down the road, just a few miles. But it was a totally different culture. Instead of going out to play baseball, you played in the Meadowlands, you explored. It became close to my heart, and I’ve just had that connection with it ever since. I saw my first egret fly over my head, and that was it. I was hooked.

Q: When did you begin birding?

A: I had a fourth-grade teacher who taught us about birds. She was an eccentric bird lady — back then, if you liked birds, you were eccentric — so I loved birds from an early age. And then going to the Meadowlands … I found it all just magical. You went out the door and you were connected to nature. Kids fished and hunted. We didn’t have any direction, we didn’t answer to anybody. We just did what we wanted to do. And not too many things in nature get better, but the Meadowlands is much better now than it was then. We might have had more of it, but you’re not seeing paint sludge, barrels, and old cars in the dumps anymore.

Q: What kept you coming back all these years? People might find the area interesting when they’re young, but then life happens. Why did you stay close?

A: I guess it was that connection. Growing up, it’s just part of who you became. My friends have moved away, but I stayed for whatever reason. It’s my home. There’s a handful of active conservationists who grew up in different areas of the Meadowlands but are still out there caring about it … and struggling to protect it. There’s something about it that gets in your blood.

Q: What do people fundamentally misunderstand about this area?

A: We still, unfortunately, have a bad reputation, which was one of the reasons we started to do Bergen County Audubon talks here. We still get Jimmy Hoffa jokes … Don’t tell me a Jimmy Hoffa joke or you’ll wind up in the water. I’m tired of it. Or, “It’s all polluted.” I mean, we still have a hard time convincing the state and federal government how important this area is, how it’s thriving. At one time, they thought it was dead. But the federal Clean Water Act of 1972 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973 brought it back. Now we have more than 300 species of birds here, including eagles, osprey, and peregrine falcons. But we need to invest more money in habitat enhancement, habitat improvement, and fighting climate change. We’re not nearly done; we have a long way to go. There’s still a lot of pressure to develop the Meadowlands, and there are still people who want to exploit it.

Q: How do you convince people that this is more than just a trash-filled swamp?

A: They’ve got to come out here. You can show them pictures, or most people see it from the train or the New Jersey Turnpike. But we’ve formed a partnership with the folks here on the Meadowlands Commission, and we do at least two walks a month, plus all our big events. We just did a butterfly day, where we got thousands of people. The birding festival is coming up, the eagle festival — all free, just to get people out here.

Q: How does the environmental health of this area compare to when you were a kid?

A: It’s night and day. It was so bad barnacles wouldn’t grow in here, you know? Whatever was in that water … there was stuff floating, there were no fish living here. It was pretty bad. But as soon as the now-banned pesticide DDT was taken out of the environment and they stopped the pollution, the fish came back. Then so did the eagles and the ospreys and the falcons. Eagles nest within a stone’s throw of here now. You never thought that was possible. You were going to have to go to Alaska to see an eagle.

Q: What’s an interesting thing about the Meadowlands that most people do not know?

A: It was once a freshwater white cedar forest. White cedar was used for everything because it was so waterproof — barrels, roofs, shingles, ships. And there’s evidence the first settlers burned out the forest because pirates were raiding ships along the river. But what I didn’t know until recently was that the ships being raided were slave ships, and the pirates were stealing the slaves. There was some law in the 1600s that if they could steal the slaves before they got to port, the slaves belonged to them.

Q: You’ve been a thorn in the side of local, county, and state officials many times when they try to develop around here. Why?

A: Somebody’s got to. Officials either don’t understand, don’t get it or don’t see the importance. And they don’t have an environmental background. They like to put things in a box where they say, “Okay, we saved DeKorte Park, we’re done.” But everything is connected to everything else, and that’s what they fail to remember. The wildlife here depends on the wildlife along the coast, or up north, or inland. This can’t survive as an island unto itself, and the wildlife can’t survive. So we’ve got to do what we’ve got to do. During COVID, the only thing people had was this. Everything was closed, they couldn’t go anywhere, and you saw the real importance of what these places mean to people. They mean just as much to people as they do to birds. A healthy environment is healthy for everybody, and that’s something officials really have to understand. You know, there’s enough pickleball courts and all that. I don’t have anything against them, but everything has to be in the right place. You don’t destroy habitat to put up a football field.

Q: How threatened is this area by climate change?

A: I certainly won’t be around to see it. But we’re not good at planning ahead. Native Americans think seven generations ahead; we don’t think seven minutes ahead. Do you want to lose it all underwater? Or do you want to start working to protect what we have? We could do that. We could do anything we want to do. If we could bring back the bald eagle, we can do any damn thing we want. We just have to have the will. That’s all.

Q: You have written that your greatest worry is — and I’m quoting one of your essays — that “too many of us are disconnecting from nature, and some children are growing up without the love of the natural world in their lives.” How do you fix that, especially in such a densely populated state like New Jersey?

A: That is the ultimate challenge, man. People ask me, “Don, what’s the biggest threat to wildlife? Climate change, right?” Well, if I can’t connect people with nature, how the heck are they going to care about climate change? Are they going out their door to work, taking their kids to school, and thinking about climate change? They’re not. But if they come out here and see what’s under threat, something clicks. Kids are the next generation, but I’ve got to get the parents to get the kids out. I used to be able to walk out my door. Now parents have to drive their kids to nature. That’s scary stuff to me. But I see projects going on in other cities, like a great project in Cincinnati, I think, where they’re building these pollinator gardens right in the middle of the city so the kids can come out and see pollinators and connect with nature. You have to start thinking more along that line — bringing nature to them.

Steve Janoski is a multi-award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Post, USA Today, the Associated Press, The Bergen Record and the Asbury Park Press. His reporting has exposed corruption, government malfeasance and police misconduct