New Jersey couple’s routine check-in ends in detention and separation

What began as another routine check-in with federal immigration authorities on Aug. 14 ended in detention for Ariel Pincay and his partner, Jamilet Macías.

Pincay, 39, and Macías, 24, had been reporting to Immigration and Customs Enforcement for four years, summoned at irregular intervals — sometimes monthly, sometimes every six months. They always went together. When they set out for their usual immigration meeting at a building just off Exit 34 on the way to Cherry Hill, they thought the visit would be like all the others.

Their aunt, who asked to be identified only as Rosa, was at work when she received a call from Macías just before 12:30 p.m. ICE had detained them both. They were told they would remain in custody until a judge could decide their fate.

Rosa waited to hear something from her nephew through the long afternoon until finally, around 5:30 p.m., her phone lit up with an unfamiliar number. She ignored it at first. But when it rang again, she picked up. On the other end was Pincay, calling from inside a detention center. Macías was there too.

“They knew they were a couple,” Rosa said. “Each time they gave them an appointment, it was for the two of them. And this time, they didn’t come back.”

In New Jersey, Pincay and Macías had carved out a fragile sense of normalcy. They weren’t legally married, but they lived as husband and wife in a rented room in Trenton, inside the home of Rosa’s ex. Both worked long hours to stay afloat. Macías cared for elderly patients just discharged from the hospital, while Pincay packed boxes in a warehouse.

“They were calm kids,” Rosa said. “They didn’t get into trouble with anyone. They were always cheerful, fun, wholesome, too, because they didn’t get into messes with anyone.”

Their lives had been shaped by the paperwork and appointments that followed them since the day they crossed the southern border and turned themselves in. ICE set the rhythm. First, it was every three months, later every six. The couple always complied. Each visit meant handing over addresses, phone numbers, and routine updates before walking back out into the parking lot.

By August, the ritual had become almost ordinary. Rosa said neither her nephew nor Macías felt particular fear that morning.

“They always presented themselves,” she said. They expected to sign in and leave as before. Instead, they never came home.

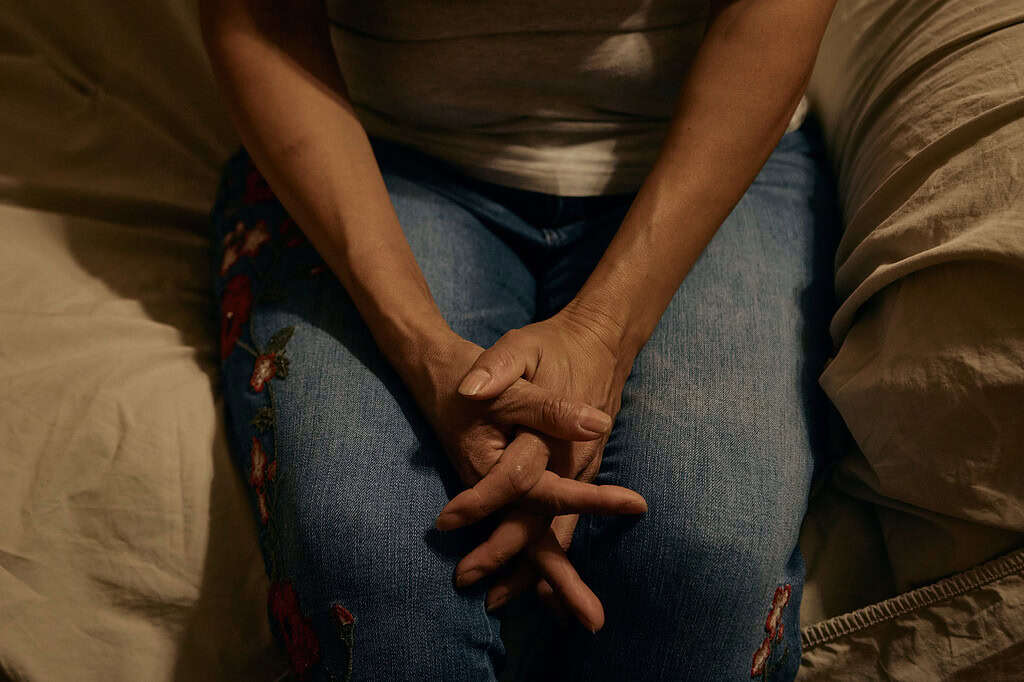

The detention shattered what little order Pincay and Macías had created. On the Sunday after their arrest, Rosa went to see them. What she found was crushing: Pincay was locked in one facility, and Macías in another.

“Their state of mind was fatal,” Rosa said. “To see them there locked up, and in the conditions that they are treated—it’s not good at all.”

Macías confided in her about the food.

“She told me that the food is terrible,” Rosa said. “One day, they even served her beans with worms.”

Work was compulsory, Macías said, and paid a dollar a day. Detainees were required to sweep floors, scrub kitchens, and wash clothes.

“They go room by room looking for people to work,” Rosa said. “And they pay them a dollar.”

Medical care, Rosa said, was just as bleak. Women with chest pains were told it was in their heads.

“They don’t treat them,” she said. “They just say it’s nothing.”

The family placed their hopes in a court date for Pincay that was scheduled for Sept. 2 at 1 p.m. But before dawn that day, ICE officers appeared at his cell. They told him nothing, only that he was leaving. When Pincay protested that he had a hearing in a matter of hours, they brushed him off.

“They told him they didn’t care,” Rosa said.

From then on, he was shuttled from place to place — first Philadelphia, then Louisiana, then another stop he could not name, and finally Mississippi.

“By the time he arrived,” Rosa said, “he hadn’t had food or water since the day before.”

In New Jersey, the family was left in limbo. They collected the couple’s few belongings from the Trenton room they had rented.

“We don’t know if they’re coming out or not,” Rosa said. “We are here waiting. But their things are already, as they say, kicked out.”

At first, Pincay and Macías tried to navigate detention without legal help. The cost was crushing, and they doubted it would make a difference.

“The lawyers are charging too much money,” Rosa said. “They don’t give certainty. And ICE isn’t giving bonds anymore. Sometimes people pay, and later they take it away. They charge the money but don’t let them out.”

Eventually, a public defender reached out to Pincay. But for Rosa, the larger fear was what awaited the couple if they were forced back to Ecuador.

“The situation in Ecuador is not good at all,” she said. Violence had become routine.”

Pincay told her that people were being killed in the streets and that going out after dark was dangerous. Just months earlier, his father had been threatened with extortion.

“They told him if he didn’t pay, they would kidnap and kill him,” Rosa recalled.

Pincay and Macías had applied for asylum as soon as they crossed the border. They filed the paperwork within the 60 days allotted by immigration authorities. What became of that application, Rosa did not know. What she did know, she said, was that her nephew and his partner had no criminal record.

“They are clean, totally clean,” she said. “They never had problems here. Not even a ticket.”

Macías, Rosa remembered, had even worked beside her at a facility caring for patients recovering after hospital stays. Rosa started her shift at 11 a.m. Macías arrived at 4:30 p.m. She was diligent, respectful, and popular.

“She had no problems with anyone,” Rosa said. “With coworkers, with the boss, everything was perfect. She was an excellent girl.”

The arrests were a blow.

“We didn’t expect something like that,” Rosa said. “We were confident nothing would happen because they had work permits. It was a very hard blow for all of us — my sisters, their friends. And for his mother, it was very hard.”

Rosa said she wants others to understand what detention meant for families left behind.

“It’s something hard, something ugly,” she said. “Families sometimes have children, and they are left abandoned. My advice is to pray a lot to God that he takes care of them wherever they are, if they are still here, or if they have already been deported, and to find strength. Better yet, for all of us Hispanics who live in these countries to unite and defend our rights, because we have rights as human beings.”

To Rosa, the targeting of her nephew and his partner felt like persecution.

“The majority that they grab are Hispanics,” she said. “They are going by appearance, not because they want to catch criminals. Supposedly, this was to catch criminals. But here they are not catching criminals, they are catching innocent people who don’t even have a crime this small.”

She questioned why her nephew was moved from Elizabeth to another state where he has no family.

“They are people without heart, without mercy,” she said. “They mistreat the people they grab. If it were really about criminals, the criminals are still outside. It’s the working people they are taking. It’s inhuman. Those who have families and work as authorities…They don’t have a heart.”

Rosa kept replaying the timeline in her mind: the detention on a Thursday in August. The abrupt transfer on Sept. 2. The long journeys by bus and plane with no food or water. The calls from unfamiliar numbers that jolted her each time. She thought of how Pincay and Macías had simply asked for the day off work to attend the appointment, never suspecting what was coming.

She thought back further, to Nov. 29, 2022, when the couple crossed the border into Texas. They spent a week locked up at the border before being released. Pincay told his aunt about the rations they were given there. A sandwich. An apple. A juice.

And then she remembered to hope Pincay and Macías carried it with them when they finally reached New Jersey.

“They never expected that they would come here,” Rosa said. “It was very beautiful. They had hope to be here a long time.”

It is that hope, Rosa said, that lingers now. It makes the silence of their absence — the empty room, the belongings packed away, the questions with no answers — all the more unbearable.

Postscript

Since the interview with Rosa, Macías decided she could no longer remain in detention at Delaney Hall. The cost of hiring a lawyer was out of reach, and relatives feared that even if a judge granted bail, ICE could revoke it, and the money would be lost.

Her family ultimately bought Macías a commercial plane ticket after authorities declined to provide transportation. On Sept. 30, at 11 a.m., ICE officers escorted her to Newark Airport and onto a flight bound for Guayaquil, Ecuador. It was not clear whether she was handcuffed during the transfer.

Macías had confided to her family her fears of being sent to faraway detention centers in states like Louisiana, where conditions are widely described as harsher. Inside Delaney Hall, she had already reported mistreatment, poor food, and a lack of medical care. One woman with heart problems, Rosa recalled, was initially denied treatment until media coverage of her case forced officials to act. That woman, too, chose voluntary departure and returned to Colombia rather than risk her health in custody.

Family members said sometimes bad press has been effective in pressuring ICE to investigate conditions at the facility. Supervisors visited in the aftermath, they said, and some improvements followed.

Meanwhile, Rosa’s nephew Pincay remains locked up in Mississippi, where conditions are worse. He is scheduled to appear in court on Oct. 14, though his family fears he may not even be transported to the hearing, a common risk that can leave detainees without their day before a judge.

Krystal Knapp is the founder of The Jersey Vindicator and the hyperlocal news website Planet Princeton. Previously she was a reporter at The Trenton Times for a decade.