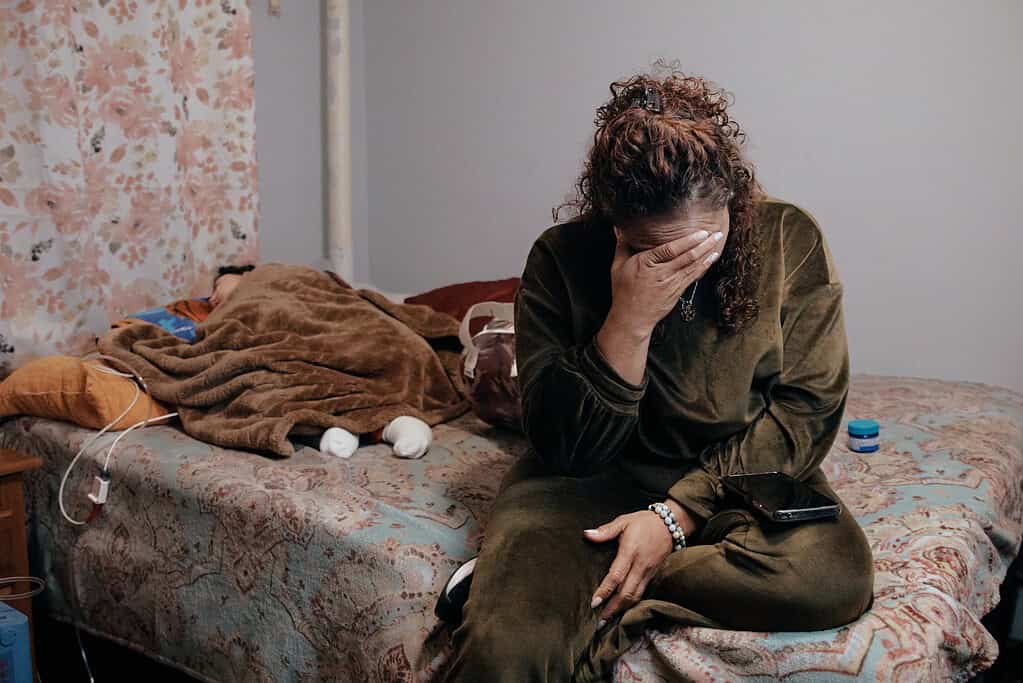

With her husband detained, a New Brunswick mother cares for her medically fragile son alone

Fanny Jakelinne Núñez rarely leaves the small room in New Brunswick where she lives with her young son, Néstor Josias.

Her days are spent monitoring his oxygen levels and medical equipment, feeding him through a tube, giving him medications, and changing his diapers. She rests only when he sleeps.

The bed fills most of the room. What remains is a narrow strip of floor where her husband, Néstor Luis Rivera Chavez, once slept in a sleeping bag so she and their son could rest on the bed.

One morning in October, her husband rose early, kissed them both, and stepped out to pick up medicine for his son and give a friend a ride to work.

He never returned. Núñez later learned that Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents had stopped him that morning and taken him into custody.

Now Núñez lives in constant fear — of being detained herself, of leaving her eight-year-old son with no one to care for him, of losing what little stability they have left. That fear keeps her confined to the small room with her son almost all the time.

Inside the room, a monitor beeps steadily, its screen glowing with numbers that signal whether her son is stable, as an oxygen machine hums beside it. Núñez uses the strip of floor next to the bed to kneel, turn, and lift her son.

The room’s only storage is a single drawer and a narrow shelf for folded clothes. There is no closet. Almost everything the family owns is within arm’s reach.

The house where they rent the room is overcrowded, shared with many other tenants in a modest neighborhood. Even under ordinary circumstances, life there is difficult. Caring for a child with severe disabilities makes it nearly impossible.

Núñez’s routine includes filling syringes with formula and slowly pressing the liquid into a gastric tube to feed her son. She kisses him, holds him close, and steadies him through each small convulsion. He cannot speak, but he listens, moaning softly, searching for her and growing distressed whenever she steps out of his sight.

He requires constant care, day and night.

When the phone rings and it is her husband calling from Delaney Hall, the boy reacts instantly. He cannot form words, but he recognizes his father’s voice, lifts his head, and makes small, excited sounds.

For Núñez, each call brings a mix of longing and pain.

She visits her husband at the ICE detention facility when she can. Activists cover the cost of her transportation. Without their help, she would not be able to make the trip.

Her son’s condition is fragile and constantly evolving. His future depends on uninterrupted medical care, proper nutrition, and a stable environment.

The family came to the United States because remaining in Honduras meant watching their son weaken without treatment. In New Jersey, he has gained weight and received the care he needs. But with her husband detained, the family has lost its only source of income. Some weeks, she cannot afford the trip to the detention center.

If her husband is deported, Núñez fears she will have no choice but to return to Honduras — a move she believes would put her son’s life at risk.

Néstor Josias was born with cerebral asphyxia, which his mother believes was caused by medical negligence. He began having seizures without warning. His breathing faltered, and his development stalled.

As he grew, scoliosis curved his spine. He lost weight because he could not take in enough food by mouth. By age 6, he weighed just 22 pounds.

His parents knew they had to leave Honduras.

“Our son was not going to survive there,” she said. “There is no help for children like him.”

The couple traveled north out of desperation, walking at times, taking buses, and sleeping on dirt floors. They entered the United States through the southern border and surrendered to Border Patrol agents. At a detention facility, Núñez said, agents threw away the baby’s milk. The family spent one night in custody before being released.

They arrived in New Jersey in May 2024. Their immigration case was active, and they checked in as required. They believed that remaining in compliance would offer some measure of protection.

They were mistaken.

They were offered a small room. It was cramped, but it was safe.

Núñez spent her days stretching her son’s back, monitoring his oxygen, and sleeping lightly, waking at the slightest change in his breathing.

Her husband worked, giving people rides and taking any job he could to cover the $825 monthly rent and their son’s needs. The family depended on him for nearly everything.

At night, after long days, he bathed quickly, changed clothes and lay beside his son on the bed, speaking softly to him and kissing him before unrolling his sleeping bag on the floor.

Then the black Suburban appeared.

On Oct. 1, Núñez’s husband left early in the morning, as he usually did.

“He always got up early to get what we needed,” Núñez said. “That morning, I only felt him leave.”

He kissed them quietly and stepped outside.

He later told his wife that he was approaching a traffic light when he noticed the black Suburban behind him. When he went through the light, the driver of the vehicle activated the flashers, he said. He assumed it was the police, and he wasn’t concerned. He did not have any unpaid tickets.

A woman approached his car. She wore a plain shirt with a small patch that read “police,” he told his wife. She ordered him to get out of the vehicle. He asked why and who she was.

She then told him he was under arrest. He protested, saying he had recently checked in for an immigration appointment.

She responded that he was an illegal, and then asked for his name.

He later told his wife he did not understand how she could say he was illegal without even knowing who he was.

Another vehicle pulled in, boxing him in. Agents threatened to break the window. He opened the door. They pulled him from the car and handcuffed him.

He told the agents he needed to pick up medication for his son, who suffers from convulsions.

They told him his wife would have to handle it herself.

He tried calling his wife, but she didn’t answer. She was still asleep with their son. He reached a friend and asked him to tell her that he had been taken.

Núñez was in shock when the friend called with the news.

“That was a hard blow,” she said. She remembers asking herself, “Now what am I going to do with my son?”

Her husband had been the only one strong enough to carry the boy, maneuver the stroller, and drive them to medical appointments. He was also the family’s sole source of income.

In the days that followed, Núñez barely ate and cried constantly. Her blood pressure spiked, and one night she was hospitalized.

Her son grew sick as well. His oxygen levels dropped, and she rushed him first to a health clinic and then to the emergency room.

Her husband cried when he heard what had happened.

“He tells me to ask for help. It’s very hard,” she said. “I am afraid, very afraid.”

The only time Núñez leaves the room is to visit her husband at Delaney Hall. She dresses her son in layers, wraps him to protect him from the cold, secures the oxygen tank, lifts him into the stroller, and carefully guides the child and his equipment down the stairs. By the time they reach the street, she is already exhausted.

At the detention center in Newark, they often wait outside for long periods.

“They leave us waiting a long time in the cold,” she said. “I don’t see them making children like him a priority.”

Inside, the waiting continues — another line, another delay — until her husband finally appears.

Núñez said that when he enters the visiting room, the boy’s body relaxes. His breathing steadies, and his eyes brighten. “He gets very happy,” she said. His father gently lifts him, adjusts the oxygen line, and rocks him against his chest.

It’s one of the rare times Núñez feels at peace.

Now it’s up to her alone to manage her son’s health care, cover rent and food, navigate immigration paperwork, monitor his oxygen, administer medications, and find ways to get to appointments she can rarely afford.

“My wish is that my husband comes out so we can continue the baby’s treatment,” she said. “So our son can walk someday. So he can talk. So he can have a future.”

If this reporting helped you understand something important about New Jersey, consider supporting it.

The Jersey Vindicator is an independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on accountability and transparency. Our reporting is funded by readers — not corporations, political insiders, or big advertisers.

Reader support makes this work possible — and helps ensure it continues.

Krystal Knapp is the founder of The Jersey Vindicator and the hyperlocal news website Planet Princeton. Previously she was a reporter at The Trenton Times for a decade.