Behind Trenton’s recreation boom: no-bid contracts, runaway overtime, government purchases on personal credit cards

Slides and swing sets for the playgrounds. Bleachers and restrooms for the ballfields and basketball courts. A resort atmosphere for the municipal pools, where flavored ices and scuba diving lessons are free, and the mayor kicks off the summer season by gamely flopping into the pool — trousers, shirt, shoes, and all.

Amid a multimillion-dollar mission to rebuild its parks, the city of Trenton is bringing life to spots that sat overgrown and vandalized for generations. Safe places to play and exercise are sorely needed in the city of 90,000 people: Trenton, the seat of state government, is an urban heat island with some of New Jersey’s highest rates of poverty, obesity, and chronic illness.

The turnaround, though, is coming at a stunning cost to local, state, and federal taxpayers. Awash in cash after decades of fiscal starvation, Trenton’s Recreation, Natural Resources, and Culture Department has awarded runaway overtime pay, steered work to friends and family members, and allowed three employees to charge tens of thousands of dollars in government purchases to their personal credit cards.

Awarded $66.6 million in American Rescue Plan Act funding after the pandemic, Trenton budgeted $8 million to improve parks. Of that, the city spent $3.2 million — more than one-third of the total — on no-bid contracts rather than soliciting quotes and choosing the lowest bidder.

At the same time, Trenton lacks cash for other pressing needs. Its water utility, which serves 225,000 people in the city and four other municipalities, is “at an extremely high risk of systemic failure” amid years of underfunding and mismanagement, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Commissioner Shawn LaTourette said at a public meeting Aug. 18. The water system’s infrastructure needs $1 billion in upgrades, state officials say.

The Trenton Recreation Department’s spending has taken place while the city operates with the oversight of fiscal monitors appointed by the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. The monitoring was a condition of the city receiving a quarter-billion dollars in taxpayer aid from Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy since 2018. In July, Trenton received a record $50.5 million from the Murphy administration, almost one-fifth of its annual budget.

“The administration’s attitude has been to throw money at these liberal, poorly run cities and look the other way,” state Sen. Declan O’Scanlon, the Republican budget officer, said in a phone interview. “The cities squander it, and it’s horrifying.”

It started with a park

Earlier this year, after the Recreation Department bungled a mile-long parks improvement project to such a degree that state environmental regulators shut it down, The Jersey Vindicator took a broad look at the department’s operations. Over four months, the news organization used the state Open Public Records Act to acquire and analyze roughly 20,000 pages of documents, including payroll data, contracts, invoices, vendor payments, audits, memorandums of understanding, Trenton City Council resolutions, internal memos, and emails.

Among The Jersey Vindicator’s findings:

- Under former Recreation chief Maria Richardson and her successor, Paul Harris, Trenton authorized at least $3.2 million in no-bid work on multiple parks, the city’s check register shows. Almost all those payments were in installments of less than $44,000, the minimum to trigger fair-and-open competitive bidding. That practice, called contract splintering, is forbidden by state law if it’s done to duck bidding rules. In 2011, Richardson won a $350,000 legal settlement from the city after she claimed that she had been fired for refusing to splinter contracts for then-Mayor Tony Mack, who was convicted of federal corruption charges.

- Below the $44,000 bid threshold, scores of other Trenton Recreation Department work opportunities — many not publicly advertised, despite the city’s own procurement rules — went to fitness instructors, caterers, dancers, musicians, snack vendors, and others who provided program services, according to the city’s check register records. Among them was Richardson’s husband, Michael Richardson, and his company, Plex Entertainment, which received almost $35,000 for DJing and other work.

- In 2023, compensation for seasonal Recreation Department and Public Works hires totaled $3.04 million, or 41% over the budget authorized by the Trenton City Council, payroll records show. Last year, the city spent $3 million, or 21% more than approved. All of that funding came from federal taxpayers via American Rescue Plan pandemic relief.

- Each year from 2021-24, Harris logged overtime, holiday work, and double-time hours that were equal to a second full-time job, according to payroll documents. Last year alone, Harris’s extra hours brought his compensation to $213,113 — more than double his regular salary. Harris, who lacks a college degree, was paid more than the mayor, the city attorney, the chief of staff, and even the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs commissioner who assigned the fiscal watchdogs.

- In 2023-24, three Recreation Department staffers were reimbursed a combined $100,000 for the use of their personal credit cards on government purchases identified as “recreation fees,” “other expenses,” and “miscellaneous supplies” in vendor payment records. Harris alone was reimbursed $53,273.52, including $20,000 that he says was for State Police background checks across multiple departments.

Asked repeatedly to discuss The Jersey Vindicator’s findings, top administration and elected officials — including Trenton Council members, Chief of Staff Jim Beach, City Attorney Wes Bridges, and Business Administrator Maria Richardson — declined to comment.

The governor’s office referred questions to the Department of Community Affairs.

“Our fiscal monitors are not there to replace or supersede the municipal professionals and their day-to-day responsibilities,” department spokeswoman Lisa Ryan said in a statement.

In May, as The Vindicator was pressing for answers, the Department of Community Affairs urged the city to undergo a forensic audit, a type of examination that looks for evidence of fraud. City officials gave The Jersey Vindicator conflicting information about whether it’s been started.

“DCA will not comment further on these matters until the forensic audit report is completed,” Ryan told The Jersey Vindicator.

Assemblywoman Verlina Reynolds-Jackson, a Democrat and former Trenton councilwoman who sponsored the legislation that gives Trenton $10 million in annual Capital City Aid, declined to comment. Her running mate and co-sponsor, Assemblyman Anthony Varrelli, didn’t return calls for comment.

‘We try to correct’

Two-term Democratic Mayor Reed Gusciora, a former municipal prosecutor, and state assemblyman, said in an interciew with The Jersey Vindicator that when potential mismanagement comes to the city’s attention, “we try to correct ourselves.”

He criticized reports in The Jersey Vindicator about city issues and posts on a Facebook civic engagement page, Trenton Orbit, run by community activist and unsuccessful Trenton City Council candidate Michael Ranallo, as “you guys just attacking the city gratuitously.”

It was a complaint by Ranallo in late 2024 that led state environmental regulators to halt work on the flood-prone Stacy Park along the Delaware River. The clear-cutting of trees and invasive plant life — done without open public bidding and at a cost of at least $270,000 — violated the Flood Hazard Area Control Act, regulators said in a Feb. 19 notice. At least five times in the past 25 years, storm-driven high water has swamped the water plant, the downtown Capitol District, and hundreds of homes.

“All unauthorized activities should cease immediately,” regulators wrote.

In April, The Jersey Vindicator reported that the main contractor had a personal connection to Richardson: He and his family had done catering jobs for private parties in her home, and had scored more work serving food at Recreation Department functions.

Gusciora said all the contractors did good work. He praised Richardson and Harris for leading the rebirth of Stacy Park and more than two dozen other sites, improving public pools, and offering recreation programs for all ages.

“I get compliments all the time about the conditions of the parks, the improvements we’re making,” Gusciora said. “We did scuba diving classes for kids. I asked one of the instructors, ‘How much does it cost to get scuba diving lessons?’ and they said, ‘The last time we checked, it was like $1,200.’ And we’re doing it for free. We do what we can. We’re a distressed city, and we’re trying to provide programming to enhance people’s lives.”

In July 2024, as the ill-fated Stacy Park project was underway, Richardson was promoted to city business administrator. Many of the Recreation Department’s spending and hiring practices continued.

In 2024-25, Richardson’s husband, Michael Richardson, and his company, Plex Entertainment, were paid $34,520 to DJ or act as master of ceremonies for city Recreation Department, and Health Department events. Michael Richardson, asked to comment outside the couple’s historic West State Street mansion, declined to discuss what he called “my private business.”

The Recreation Department also still regularly reimbursed three staffers, including Harris, for government purchases, vendor records show. Harris said the city won’t allow employees to have government purchasing cards, and the department often needs supplies “on a real-time basis.”

Many other Trenton departments, though, use an Amazon account, which had $250,000 in charges in 2023-24 — including tens of thousands of dollars in Recreation purchases, according to vendor activities reports. Asked why the three employees shop for the city with their own credit, Gusciora said: “Amazon is more expensive than other vendors.”

As a government entity, Trenton is tax-exempt. Using personal charge cards rather than an official account, the city employees potentially threw away as much as $6,625 in sales tax.

‘No one pays anything’

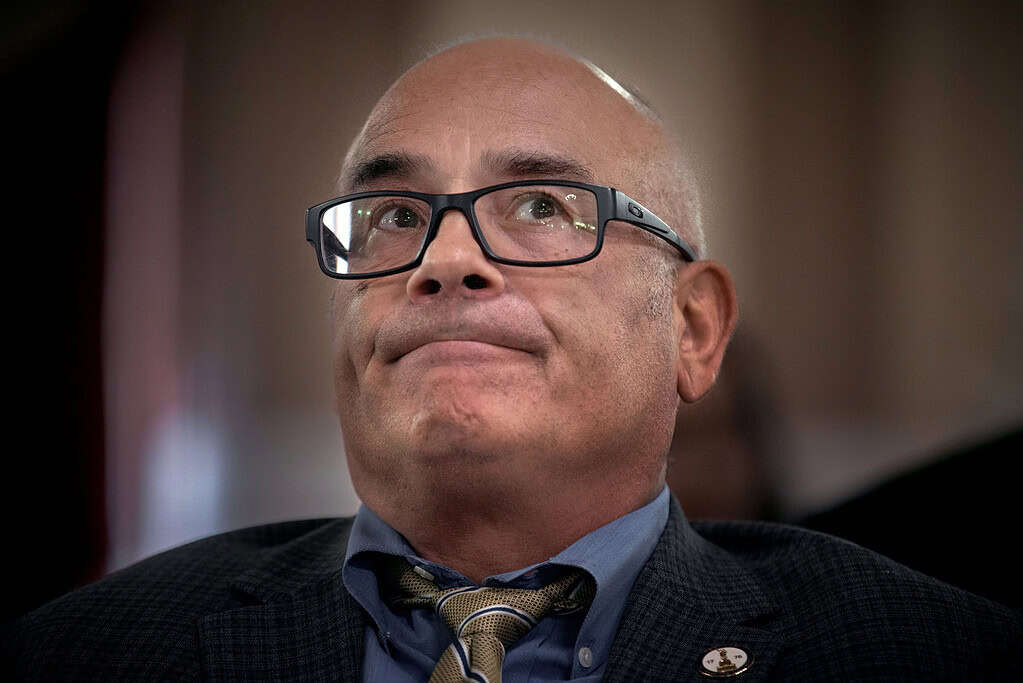

In an interview, Harris told The Jersey Vindicator his broad experience in city government has made him the go-to staffer across many departments. Hired as a stock clerk for the city in 2012, Harris had a series of jobs in the Trenton Finance Department before he became a Recreation Department management assistant, reporting to Richardson, in 2022. In July 2024, Richardson was named business administrator, and Harris replaced her.

Harris said his main focus is on five municipal pools.

“What you want to do is give them a country club pool experience,” Harris said of patrons. “Life jackets, lawn chairs, Italian ice. No one pays anything.”

Harris takes no vacation time, payroll records show, and has donated some personal hours to other employees, he said in an email. He’s a taskmaster, he said, who demands excellence from his staff, and he recalled how he once scolded workers for “taking too long to clear a park,” and requesting extra hours to finish the job.

“‘No, you can’t do it on overtime,’” Harris said he told them.

At the same time, Harris defended how the Recreation and Public Works departments’ overtime for temporary summer hires ran $6 million over budget for two years. That money, he said, stayed local, and went to residents of a city with historically high unemployment and few job opportunities.

The mayor noted that if Trenton didn’t spend the pandemic aid by a strict federal deadline, the money would be clawed back.

Harris’s own long workweeks lead to fat paychecks.

Over five years, Harris has more than doubled his salary by working extra hours, bringing his 2020-24 total compensation to $871,483, payroll records show.

- 2020: Regular pay was $41,880, and holiday, overtime, double time, and longevity added more than $65,000.

- 2021: Regular pay was $43,021, and extra pay was more than $75,000.

- 2022: Regular pay was $62,376, with an additional $123,000 in overtime pay.

- 2023: Regular pay was $75,239, with an additional $132,000 in overtime.

- 2024: Regular pay was $98,332. In just six months of eligibility for overtime and double time, he received $104,000 in that category.

Folding clothes on OT

In precise detail, in quarter-hour increments, Harris tracked his tasks on his time sheets and in a daily journal.

“Watering poinsettias,” Harris wrote on a December 2019 timecard. “Observation: Could get no one to care about them dying or dry.” Other times, he entered data on the city website, designed flyers, and visited homes to make sure they were delivered by the U.S. Postal Service, processed payroll, reviewed employee drug screening results, shopped for paint, checked whether a contractor had dug fence footings to a correct depth, compared pricing for a rental garbage truck, drained and power-washed municipal pools, organized supply closets, folded uniforms, and, over several months, assembled an employee phone list.

Alongside notes on union contract negotiations, he wrote: “Trying to get data to compile accurate data without proper access is an ongoing issue. Some BS. So many hours creating reports that already exist.” For that particular two-week pay period, Harris reported 70 regular hours and 82.25 overtime hours.

Gusciora, the mayor, said City of Trenton staffing never recovered from eight years of massive budget cuts by former Gov. Chris Christie, a Republican who left office in 2018. Gusciora praised Harris for what he called “filling gaps” across many departments.

Civil service employment rules, though, prohibit “out-of-title” work, because those duties belong to clerks, laborers, and other non-management, lower-paid staff within the merit system. The practice is forbidden by two Department of Community Affairs memorandums of understanding that outline state aid stipulations.

Harris said he wasn’t working out of title, because his job description includes the phrase “does other related duties.” Leadership of AFSCME Local 2286, which represents city workers, didn’t respond to emails, voicemails, and text messages from The Jersey Vindicator.

“I’m not taking anyone else’s overtime,” said Harris, who identified himself as the local’s interim treasurer. “They’re right alongside me, folding T-shirts, and getting overtime, too.”

Elise Young, a veteran journalist with bylines for Bloomberg, The New York Times, the Bergen Record and elsewhere, lives in historic Trenton. She is the author of Victim EY, a chronicle of a brutal street attack and its aftermath, at EliseYoung.substack.com. She can be reached at EliseRYoungATgmail.com