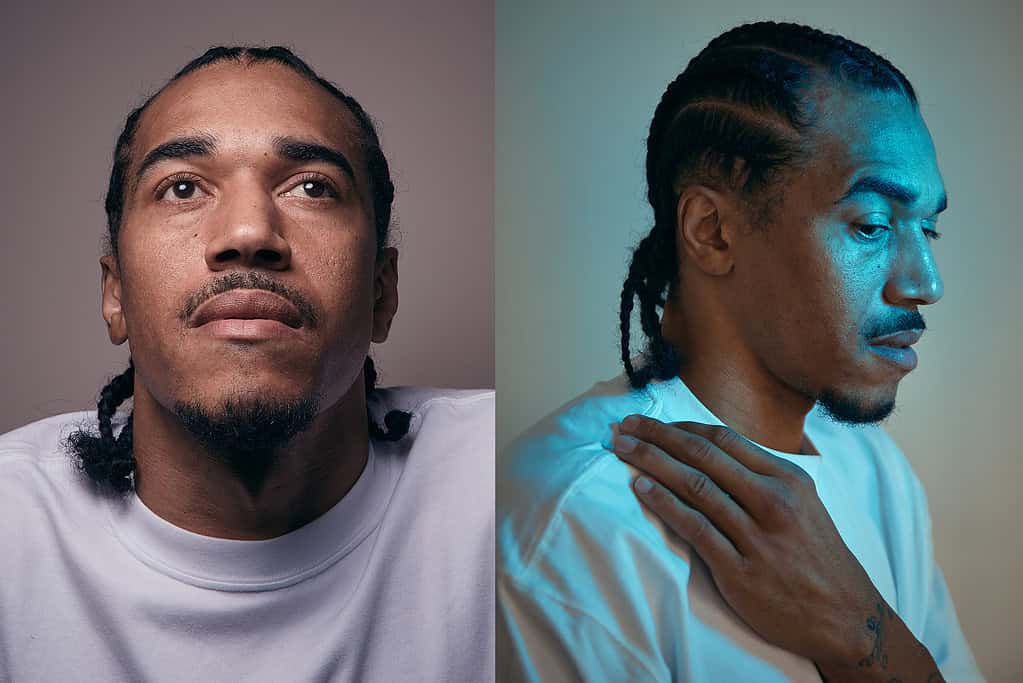

Five years after being shot by Bloomfield police, Jeffrey Sutton is still seeking justice

Jeffrey Sutton lifts his ravaged left arm and studies the scars etched into his brown skin — silent reminders of the damage wrought by a half-dozen hollow-point bullets fired by Bloomfield police.

Sutton’s no angel. He’ll be the first to tell you about his roguish life, inglorious mistakes, and lengthy arrest record. But what happened to him during a traffic-stop-gone-terribly-wrong one November day in 2020 still haunts him, even as he sits in his Newark attorney’s conference room five years later.

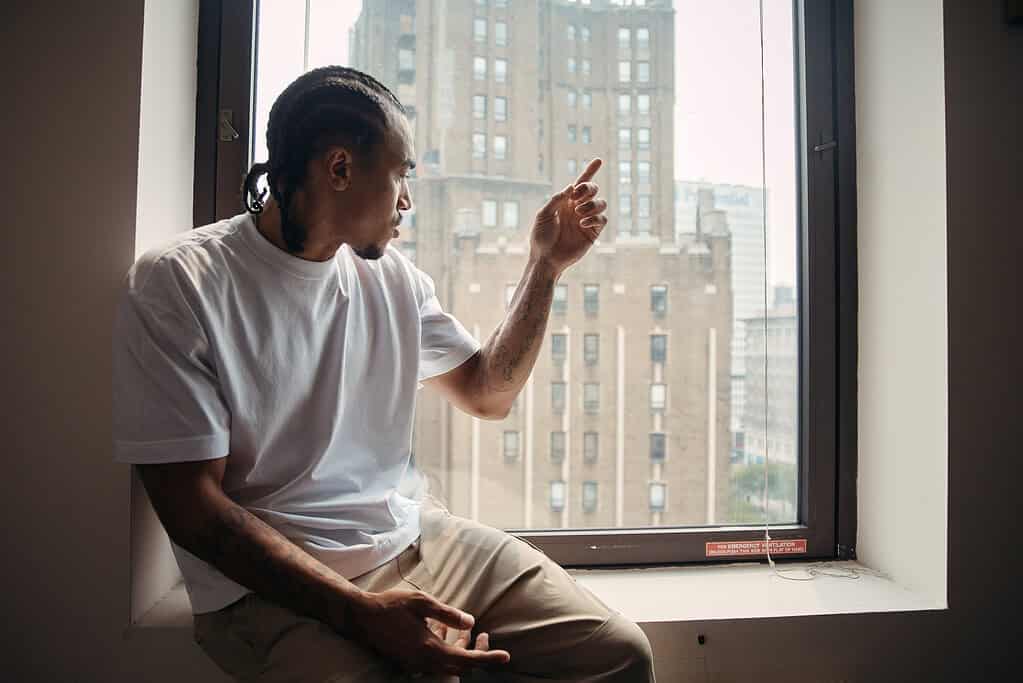

“When I got out the car, I had a bullet hanging out here, here, and here,” Sutton, a 42-year-old father of five from West Orange, told The Jersey Vindicator as he pointed to the now-healed wounds. “The bullets here and here — I took out the shell myself before I made it to the hospital.”

Now he’s the plaintiff in a federal civil lawsuit against Bloomfield and its police department, whose officers in the incident allegedly lied afterward, claiming Sutton hit them with his car when he tried to escape just before they pulled their triggers. Videos of the incident later proved that no such thing happened.

Almost everyone except Sutton has moved on.

None of the cops were indicted, and some have already retired.

Others have been promoted, including Gary Peters, who now serves as the police department’s deputy chief.

But the soft-spoken Sutton remains mired in the past, still dealing with the physical toll the bullets exacted as he tries to steer his life back onto the straight and narrow.

“My doctor told me that when they shot me here, it basically blew the nerves out the end,” Sutton said, gesturing to one of the scars on his forearm. “The nerves are shot. I can’t do much. I’m an HVAC technician, but working in this field … It’s like, how can I really work and pick up ducts and dealing with certain machinery and equipment with nerve damage?”

His grip tires easily, and it’s tough for him to extend his left hand. The former high school baseball and basketball star sometimes loses feeling on one side of the weakened limb.

He’s been trying to rehab the injuries. But it hasn’t been easy.

“I’ve been doing [physical therapy] at home, I’ve been going to doctors’ appointments and following up as much as I can,” he said. “But with my limited insurance, how much [can I do]?”

The potential winnings from his civil lawsuit, which was filed in Newark federal court three years ago and accuses the Bloomfield police of numerous civil rights and constitutional violations, might alleviate some of that.

Depositions only wrapped up in August, and it’s still not clear if Bloomfield plans to settle the case or fight it out in a courtroom.

Either way, Sutton’s attorney, Michael Ashley, said the cash isn’t paramount. Sutton wants to take the cops to task for their actions that day.

“Accountability is the biggest thing,” Ashley said. “Money is nice, right? Everyone likes money… but at the same time, there’s an acknowledgement of your injury.”

“Certainly, someone getting fired or reprimanded would probably feel good as far as the accountability piece goes,” Ashley said. “But I think it can be similarly fulfilling if, behind the scenes, the town council had to have a serious conversation with these people and say, ‘Look, you guys are costing us money.’”

‘I knew if I stayed, I was dead’

Sutton’s case stems from an incident that erupted at about 1:45 p.m. on Nov. 9, 2020, as he drove his 2015 Mercedes E350 down Bloomfield Avenue, according to his civil lawsuit.

Unbeknownst to Sutton, an automatic license plate reader perched along the road flagged his car as a so-called “felony vehicle” that had been used in a crime, which led local police to swarm his Benz.

An unmarked police SUV even cut across two lanes of traffic to head off Sutton’s sedan, which was headed in the opposite direction.

Two men in suits and another wearing a white shirt — later identified as then-Capt. Gary Peters, Capt. Patsy Spatola, and Sgt. Mark Moskal — burst out of the black truck with their weapons drawn and pointed them directly at Sutton’s head, according to both the lawsuit and footage of the incident.

Sutton had indeed been involved in an eluding incident a week earlier, and reportedly had open warrants for his arrest.

But the cops didn’t know that, Ashley said.

They only knew the plate reader flagged a gray Mercedes, but had no idea to whom the car belonged, who was driving, what crime they were accused of committing, or even what type of car it was beyond the make.

And Sutton said he had no idea that the gun-toting, plainclothes men who raced around his car were actually cops.

“I was scared sh—less bro, I’ll be honest with you,” Sutton said. “I was like, ‘Who the freak is this? And what’s going on?’ I never knew [they were cops] … I didn’t know what was transpiring, I had never seen a takedown like this.”

Sutton had been riding with the mother of one of his children, but she quickly jumped out of the car in terror.

He slammed his car into reverse and pulled away, the videos showed, although he said he stopped when he realized the three men were cops.

But that didn’t assuage his fears. George Floyd had just been murdered in the street six months earlier, and Sutton had a “heightened fear of unprovoked attacks perpetrated by law enforcement,” according to his lawsuit.

“This fear was further fueled by the unnecessary escalation of the situation and overly aggressive response by the Bloomfield Police Department,” reads the lawsuit. “The plaintiff was wholeheartedly terrified … and genuinely feared for his life during the entirety of the ordeal.”

What followed was a communication breakdown of epic proportions as more cops mobbed the scene.

Some officers tried to lure Sutton out of the car. One tried to shatter his window with his baton, while Peters kept his handgun trained on Sutton and allegedly screamed that he was more than willing to pull the trigger.

“[Sutton] verbally pleaded for his life, assured officers that he did not have a weapon, and begged them to put theirs away,” according to the lawsuit.

At one point, he got so scared that he climbed into the car’s backseat.

“I was petrified,” Sutton said.

Moskal and Spatola seemed to recognize Sutton’s willingness to comply. They holstered their guns and tried to calm him by saying they could safely arrest him, the suit said.

But Peters was allegedly a different story. He’d positioned himself squarely in front of Sutton’s Benz and leveled his pistol at Sutton’s head, all the while spewing obscenities, according to the lawsuit.

“I was going to jump out the back seat and run to this officer on this side,” Sutton said, pointing to a tablet screen as a video of the encounter played. “But I’m like, if I jump out, will he shoot me in my back?…I believe Peters just wanted to hold court in the streets that day.”

In the end, Sutton decided to pilot his Mercedes around the cops. He hit a civilian’s truck and took off down the busy thoroughfare. That prompted the officers to unleash a flurry of bullets that shattered and scarred Sutton’s left arm.

“In light of Peters’ continued threats, Plaintiff believed that he would imminently have lethal force used against him and tried to navigate his automobile around the officers to safety,” reads the lawsuit. “His belief was unfortunately realized when Captain Peters and Officer [Raymond] Diaz fired their service weapons at Plaintiff, striking him multiple times.”

“None of the BPD officers had witnessed Plaintiff commit any violent act or possess any weapon,” according to the lawsuit. “The shooting of Plaintiff was without justification, adequate provocation, or just cause and constituted an act of excessive force.”

Still, Sutton thinks taking off was a better move than staying on scene.

“Had I not pulled off … I definitely feel like I was gonna’ be murdered right there,” Sutton said. “I knew if I stayed there, I was dead…I never did anything to law enforcement.”

Cops eventually tracked Sutton down and arrested him.

They later justified their use of force in internal reports by claiming Sutton had tried to run them down — and hurt at least Spatola, Diaz, and Moskal in the process, according to the lawsuit.

They charged him accordingly, jailing him and slapping him with six offenses, including aggravated assault on a police officer, that could have led to his imprisonment for years.

But seven months later, video footage of the incident obtained through a Kane In Your Corner News12 investigation proved Sutton never hit anyone. The footage showed that the cops had pulled the trigger as Sutton was driving by. He wasn’t approaching them.

Most of the charges were dropped following the report, and Sutton pleaded guilty to a single count of third-degree eluding in a deal that wrapped up the case and other outstanding charges from other run-ins with the police, Ashley said.

Sutton ended up spending nearly 38 months in jail.

The question remains, however: Why did the cops write on their reports that he’d injured officers when they had access to the same footage that would eventually vindicate him?

According to the lawsuit, it was because they wanted to “improperly shield the [officers] from liability for their unlawful exercise of excessive force against him, racial animus, and other constitutional violations.”

In other words, the cops allegedly conspired to make it sound like Sutton was a threat to life and limb because it justified the shooting, according to his attorney.

“Ultimately, I mean, that’s what they’re going to have to say,” Ashley said. “If I’m a police officer and I use deadly force … if I don’t say I’m in fear for my life, I’m automatically wrong, it’s case closed. So they have to say that.”

Sutton said he never even thought about running the cops down.

“No — heck no,” he said. “I had no reason to. I never did anything to law enforcement. Eluding? I may be guilty of doing that. But I never intended on pulling off on them officers … I never intended on having any altercation.”

“I cut the car off, and I said to myself, ‘I’m going to jail,’” he said. “But [Peters] wouldn’t allow it … he was saying he was going to blow my head off, and if I keep fidgeting, if I reach for the door handle, he’s going to shoot. I didn’t know what to do.”

None of the cops faced prosecution for either the shooting or the false reports.

A grand jury declined to indict them in October 2021, the Essex County Prosecutor’s Office said. This disappointed both Sutton and police transparency advocates like Hackensack attorney C.J. Griffin.

“The old adage is that a prosecutor can indict a ham sandwich,” Griffin told News12 at the time. “But for whatever reason, when it comes to investigations of police shootings, they can never obtain an indictment.”

The prosecutor’s office also reviewed Sutton’s allegation of false reporting and “found insufficient evidence of criminality,” spokesperson Carmen Martin of the prosecutor’s office told The Jersey Vindicator in an email.

Martin ignored further follow-up inquiries and never responded to a request for an interview with county prosecutor Theodore Stephens II.

Bloomfield Police Chief George Ricci and Deputy Chief Gary Peters did not respond to repeated requests for comment, nor did township Mayor Jenny Mundell or any member of the governing body.

The attorneys representing the officers also did not respond to a request for comment.

For his part, Sutton wants to finally move on, but the shooting has left him feeling like the system is rigged.

“Peters got promoted, and I’m sitting here suffering,” Sutton said. “It’s definitely taken a toll on me mentally … I never thought I’d get shot — not by a cop. I think about it every day.”

“Every day I wake up at five or six o’clock, I think about it,” he said. “Remembering how he took aim, I knew I wasn’t supposed to make it … I’m blessed to be here.”

If this reporting helped you understand something important about New Jersey, consider supporting it.

The Jersey Vindicator is an independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on accountability and transparency. Our reporting is funded by readers — not corporations, political insiders, or big advertisers.

Reader support makes this work possible — and helps ensure it continues.

Steve Janoski is a multi-award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Post, USA Today, the Associated Press, The Bergen Record and the Asbury Park Press. His reporting has exposed corruption, government malfeasance and police misconduct